Reports and articles

Has manufacturing been underestimated?

Published on June 12th 2019

How much does manufacturing really matter to the UK’s economic prosperity? National statistics report that manufacturing activity contributes only 10 percent to GDP, with a trend towards deindustrialisation over the past decades seeing services replacing manufacturing as the future engine of growth. But a new report from researchers at the University of Cambridge explains why this picture is misleading, and why the real economic value of manufacturing is in fact significantly higher.

The manufacturing sector plays a significant role in the UK economy. As measured in the national accounts, it provides over 2.7 million jobs, makes up 49 percent of UK exports, and contributes 66 percent of all UK R&D business expenditure (Office for National Statistics, 2018). However, based on current measurements, manufacturing contributes only around 10 percent to national GDP, apparently dwarfed by the services sector which makes a 70 percent contribution to GDP.

But new research indicates that the picture is more complex than these figures suggest. Emerging technologies, business models and value chain structures are changing the manufacturing landscape. There have been radical alterations not only in how we make things, but also in how we innovate and in how we capture value from manufacturing-related industries. As manufacturing evolves, so too do definitions of manufacturing and industrial systems. In turn, policymakers need new ways to assess the value of manufacturing activity.

Dr Jostein Hauge from the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Policy at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Manufacturing explains:

“The difficulty lies in trying to measure manufacturing as a single category. It is inherently more complex. Economic value of manufactured goods increasingly depends on activities that are officially categorised as belonging to other sectors of the economy. A range of manufacturing-related services are excluded from the manufacturing category.”

For the purposes of developing industrial strategy, policymakers need to understand manufacturing in a broader context, with the ability to identify interdependencies across activities which are currently separately categorised.

Clare Porter, Head of Manufacturing at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, comments:

“The official statistics fail to incorporate fully the role of UK manufacturing in supporting national economic competitiveness and growth. In particular, the official manufacturing statistics do not include the additional value added or jobs generated by services across manufacturing value chains. Many of these services would not thrive, or even exist, without UK-based manufacturing.

It is important that policymakers understand this bigger picture and the dependencies between recorded manufacturing activity, industrial services and capabilities so we can develop policies and programmes that will support long term UK industrial competitiveness and growth.”

A new report ‘Inside the Black Box of Manufacturing’ by Dr Jostein Hauge and Dr Eoin O’Sullivan reveals that the economic contribution of manufacturing is more significant than is conveyed by conventional methods of counting. The report discusses how manufacturing is defined, how it is changing, its interdependencies, and recommendations for policymakers shaping the UK’s industrial strategy and policy agenda.

What is ‘manufacturing’? A systems view

So how should we be more accurately conceptualising and counting manufacturing in the economy?

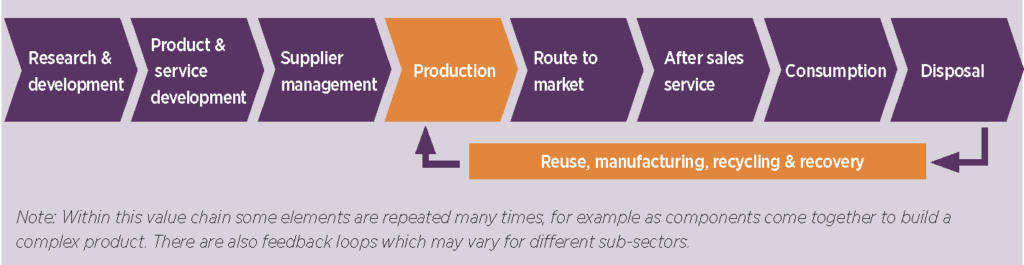

National manufacturing activity, as normally reported within the national accounts, is measured by counting the output of firms whose main industrial activity involves the transformation of materials or components into new products, and/or the assembly of components or subsystems into new products.

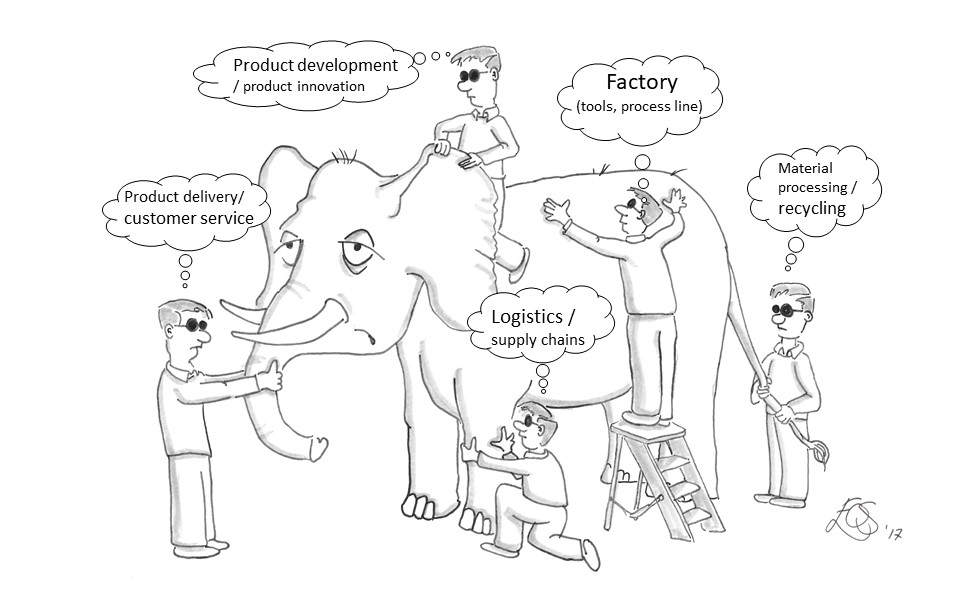

But a key challenge for policymakers and national economic statisticians is that the economic value of many manufactured goods depends on activities beyond factory-based production. Most production systems today are highly complex, and rely on contributions from a range of ‘industries’, as we traditionally think of them.

As Eoin explains:

“Our aim is to highlight the systems-nature of manufacturing. Think about the functioning of a manufacturing system like the functioning of a complex organism, like the human body. The functioning of the human body relies on cooperation between interdependent biological sub-systems — like the circulatory system, the digestive system, the immune system, the nervous system, the muscular system, the respiratory system, and so on. Just like the human body, the functioning of a manufacturing system relies on cooperation between interdependent sub-systems as well.

The central value chain, which consists of R&D, design, production, distribution, and after-sale services, needs timely provision of technical services, like analysis, testing, and logistics. It also needs timely provision of specialist professional services, like regulatory services, intellectual property services, investments services, and consultancy services. And it needs supply of materials, components, and other manufactured inputs, like machinery, equipment, and tools.”

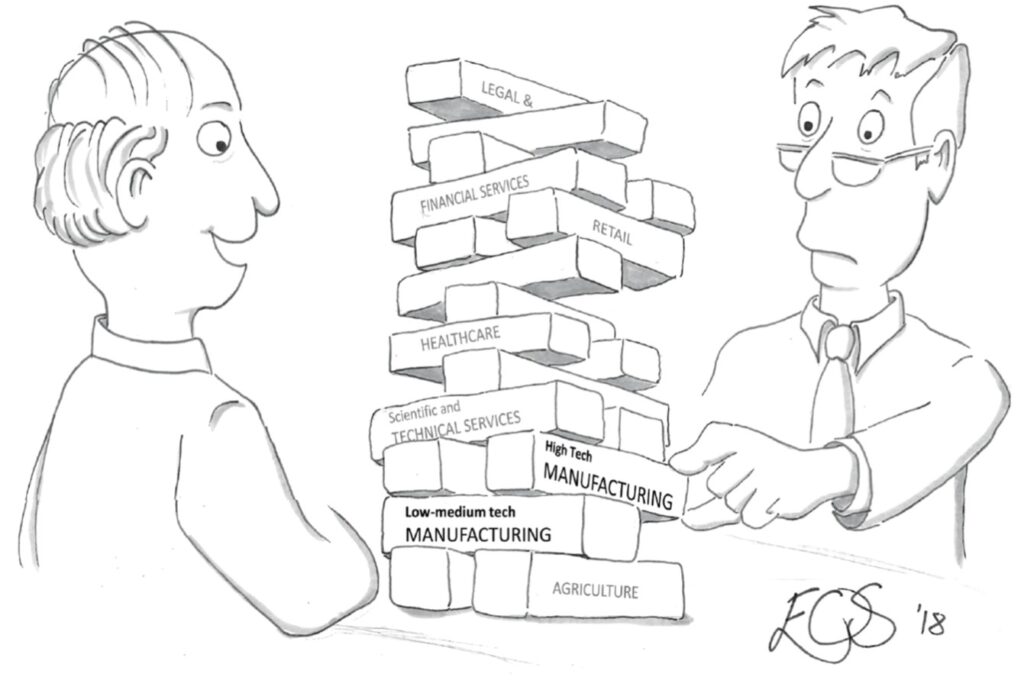

Problems with current classification

In the UK, economic activities are classified using standard industry classification (SIC) codes. This means that a company that both makes and delivers a product will be classified into either manufacturing or services, not both, depending on the number of people working in each category. Consequently, shifts in the number of companies counted as ‘manufacturing’ can be caused by changing outsourcing arrangements rather than an actual change in the economy’s production structure.

Another cause of distortion is that productivity in manufacturing grows faster than that of services. In many operations settings, more units can be produced by a smaller number of people. A consequent shift in employee balances – fewer needed in production, more needed in related services – can suggest that manufacturing’s value has dropped, whereas the reality is that its productivity has increased.

A UK government report estimates that up to 10 per cent of the fall in manufacturing employment between 1998 and 2006 in the UK may be due to this reclassification effect.

To compound the issue, the current classification system reflects an increasingly outdated understanding of what activities are involved in manufacturing. Advanced manufacturing involves new types of factory input, production stages and industrial processes, including integrated software solutions, design of synthetic materials, and recycling and reuse of materials, to name a few.

Crucially, there are many activities classified as ‘services’ which actually require manufacturing-specific technical knowhow, like R&D, industrial design, analysis, and testing. Additionally, professional services, like regulatory services, intellectual property services, investment services, and consultancy services, are increasingly tailoring their needs to specific manufacturing industries.

Jostein comments:

“We argue that many of these services (at least the technical services) should ‘belong’ to the manufacturing sector for the purpose of industrial strategy.”

Why does this matter?

Seamus Nevin, Chief Economist at Make UK, states:

“Despite the common sense of declinism, manufacturing businesses contribute nearly 3 million mostly high-paying jobs, half of UK exports, the bulk of this country’s R&D spend, and the UK is today the 9th largest manufacturing economy in the world in GDP terms. And, as this report shows, those figures are probably significant underestimates.

An increasingly outdated understanding of what modern manufacturing actually is means policymakers have neglected the sector in the misguided belief that services, not manufacturing, is where the future potential for innovation and productivity growth lies. This report is a clarion call for politicians of all parties to update their understanding and recognise the central importance of manufacturing not only to local regions but to the wider UK economy as well.

The Government has set out a modern industrial strategy which will be at the centre of the UK economy post Brexit. It is now essential that there is cross party support to deliver on this to ensure we meet the new technological challenges of digitisation, as well as the societal challenges to which manufacturing, science and engineering will be at the heart of solving.”

Eoin agrees:

“If the economic contribution of manufacturing is underestimated, the implications could be severe. First, industrial strategy will fail to target all those firms that should be targeted. Second, if manufacturing does not appear to be important for the economy, it could mean that industrial strategy will become neglected on the government’s policy agenda. A well-designed industrial strategy is vital for the prosperity of the UK economy.”

Understanding the problems with current measurements raises important questions.

First, has the extent of deindustrialisation been overstated?

In the UK, the gross value added of manufacturing in GDP has declined from 17 percent in 1990 to 10 percent in 2017. This clearly indicates that the UK is going through a process of deindustrialisation. But how accurate is this rate of decline?

Jostein comments:

“We are not arguing that deindustrialisation in high-income countries, like the UK, is not happening. But our conclusion is that the manufacturing ecosystem is larger than what the industry classifications data on manufacturing reveal.”

Second, is the future potential of manufacturing being underestimated?

The trend of deindustrialisation in the UK and other high-income countries has spurred a discourse which claims that services, not manufacturing, is where the future potential for innovation and productivity growth lies. This view fails to shed light on interdependencies between manufacturing and services, but could have a major influence on national investment decisions.

Third, how do we interpret the likely impact of digitalisation?

Digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing, and the industrial internet of things, are becoming more pervasive in manufacturing processes. However, as the report points out, evidence of the impact of how these technologies are affecting manufacturing is scant, which signals a need for research to devote more attention to digitalisation.

More accurate numbers to inform industrial strategy

The report’s main recommendation is that for the purpose of industrial strategy, the current classification system needs to be reorganised. Firms should be associated with those sectors of the economy to which their productive capabilities contribute. This means that, for example, Arm, which is a UK semiconductor and software design company, should not be simply classified as a ‘services’ activity, but should be identifiable as a critical part of the UK manufacturing industry ecosystem.

Jostein concludes:

“Essentially, we are arguing for a system of analysis that is more useful for policymakers than the existing system of industry classification codes, that can show how firms have self-organised around a common economic value proposition.

Policy therefore needs to have a more holistic sense of the system. Industrial strategy should be designed with not only manufacturing firms in mind, but also all the services firms that are part of and serve industrial systems.

It is essential for policymakers to invite these services firms to the table when they conceptualise their national industrial strategy. We also hope that this will provide compelling reasons for policy practitioners and national economic statisticians to believe that manufacturing still is and will keep being an integral driver of technological development, productivity growth and economic prosperity.”

The report Inside the black box of manufacturing: Conceptualising and counting manufacturing in the economy has been prepared for the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Authors:

Dr Jostein Hauge, Research Associate, Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Policy at the Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge

Dr Eoin O’Sullivan, Director of the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Policy at the Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge

Related resources

19th February 2026

Unpacking the France–UK productivity gap: a sectoral analysis

13th February 2026

The UK Manufacturing Dashboard: a tool for evidence-based industrial policy

News | 6th February 2026