Reports and articles

Why manufacturing is still key to China’s development goals

Published on December 1st 2025

*Originally published in the South China Morning Post.

Senior Policy Analyst Zongshuai Fan explains how revitalising manufacturing – from advanced sectors to upgraded traditional industries – remains vital to achieving China’s 2035 development vision.

This blog is also available in Chinese

中文版

As China drafts its 15th Five-Year Plan, it faces the realities of slower productivity growth, an ageing workforce and uneven industrial upgrading. The country’s latest strategies signal a shift towards productivity-led growth anchored in manufacturing strength.

Following the Communist Party of China’s (CPC) recent Fourth Plenary Session, debate has intensified over the direction of the country’s economy, with manufacturing remaining a central pillar of Beijing’s ambitions for the coming decade.

The CPC Central Committee’s Recommendations for the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-2030), released on October 28, reaffirm the Party’s goal for China to join the “middle ranks of developed countries” by 2035, measured by GDP per capita — a vision first outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan and originally proposed by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s.

While no official benchmark has been defined, a State Council study estimates the target at about US$30,000 per capita (in 2020 prices) by 2035. With GDP per capita currently at US$13,303, China would need to roughly double its income level within the next decade to reach that goal.

As economist Justin Yifu Lin has noted, differences in GDP per capita between China and mid-level developed economies largely reflect disparities in labour productivity, measured by output per employee. Productivity growth, therefore, will be a key driver in achieving China’s 2035 target, and has been identified as one of the main objectives in the Recommendations.

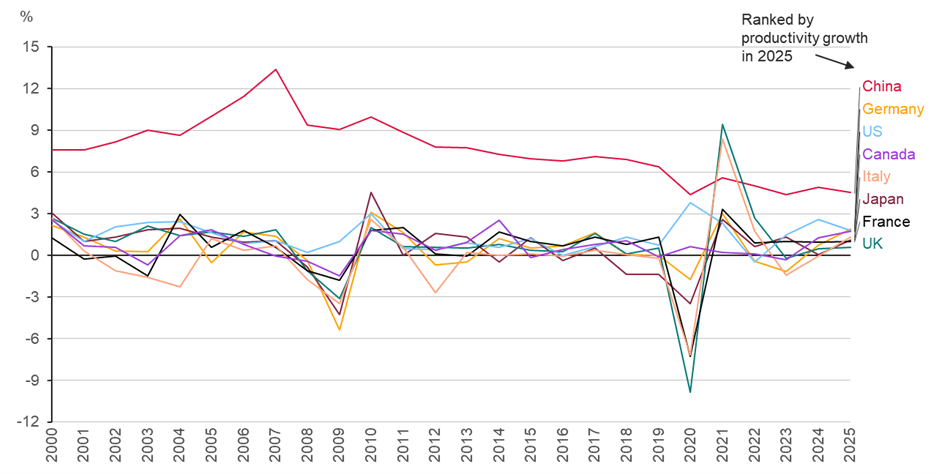

Although China’s labour productivity growth has consistently outpaced that of the G7 economies since the early 2000s, its momentum has slowed markedly since the 2008 global financial crisis. Growth is projected to ease to around 4.5 per cent in 2025, underscoring the challenge of doubling GDP per capita by 2035.

Figure 1 Labour productivity annual growth rate, China versus G7 countries, 2000-2025

Source: ILOSTAT. Annual growth rate of output per worker (GDP constant 2021 international $ at PPP) (%) (accessed October 2025)

Manufacturing holds the key to boosting China’s overall productivity. Since 2023, when the country’s labour productivity growth fell to its lowest level this century, Beijing has rolled out a raft of policies to promote what it calls “new quality productive forces.” The strategy doubles down on developing emerging industries and upgrading traditional sectors to raise productivity and, ultimately, sustain economic growth.

Emerging industries are concentrated in medium- and high-tech manufacturing, such as new-energy vehicles, aerospace and advanced machinery production. Meanwhile, traditional industries continue to form the backbone of China’s manufacturing base, accounting for about 80 per cent of total employment and value added.

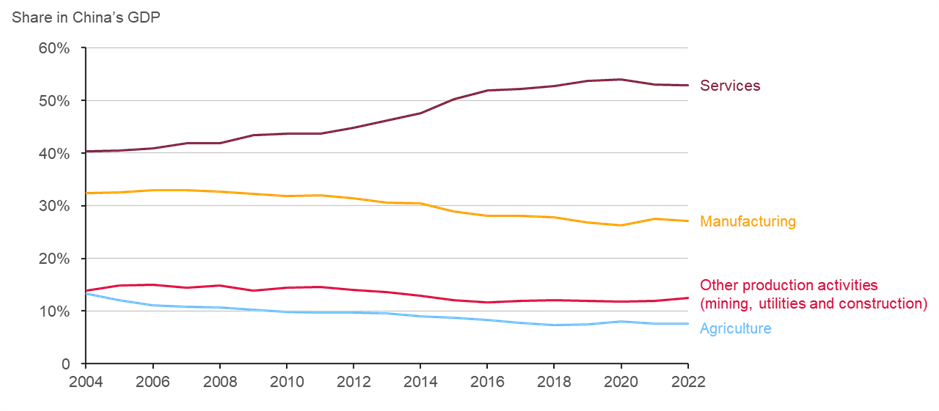

From a structural perspective, however, manufacturing’s contribution to the economy has been steadily declining as the services sector expands its share of overall activity. Official data show the manufacturing share of GDP fell from around 33 per cent in the early 2000s to 27.1 per cent in 2022. Census data indicate its share of total employment has remained largely stagnant, slipping by 0.1 percentage point between 2015 and 2020, compared with a 1.3-point increase between 2010 and 2015. As a result, Beijing faces mounting challenges in making manufacturing a stronger engine of growth over the next decade.

Figure 2 Sectoral contribution to China’s GDP, 2004-2022

Source: China’s National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook

The movement of rural migrant workers — defined as individuals whose household registration (hukou) remains in rural areas but who engage in non-agricultural work locally or elsewhere for at least six months a year — offers important clues to labour shifts out of manufacturing. This group accounts for about 80 per cent of total manufacturing employment. According to the National Survey Report on Rural Migrant Workers, their number reached 299.7 million, up 33 per cent since 2008.

Workers leaving manufacturing have mainly moved into service subsectors with lower productivity levels, including wholesale and retail trade, transport, storage and postal services, accommodation and catering, and household services and repair. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the share of rural migrant workers employed in manufacturing has fallen by 9.3 percentage points, while their share in these four service subsectors has risen by 7.1 points.

Beyond losing appeal among younger workers, China’s manufacturing sector faces growing pressure from an ageing labour force. Among rural migrant workers, the share aged over 50 has surged from 11.4 per cent in 2008 to 31.6 per cent in 2024. This demographic shift underscores the challenge for Beijing to raise productivity while maintaining sufficient employment in manufacturing, avoiding both a labour exodus into lower-productivity service sectors and the risk of large-scale unemployment.

In response to these structural challenges, the Recommendations state that “the share of manufacturing in the national economy should be kept at an appropriate level” during the 15th Five-Year Plan period. By comparison, the relevant narrative in the 14th Five-Year Plan is to keep the share of manufacturing “basically stable.”

An appropriate share of manufacturing in GDP is essential to sustaining productivity growth and raising GDP per capita. In high-income economies, manufacturing continues to play a significant role, accounting for 27 per cent of Ireland’s GDP, 18 per cent in Switzerland, 16 per cent in Singapore and 18 per cent in Germany. Although manufacturing represents just 10 per cent of the US economy, revitalising domestic manufacturing has become a key priority for the Trump administration, underscoring its strategic and political significance.

For China, the question is not whether manufacturing endures, but how it evolves. Many of its high-tech industries already rival those of advanced economies, yet intensifying global competition and the drift of workers into lower-productivity sectors risk slowing the gains that once powered its growth. The challenge is to turn China’s industrial might into sustained productivity growth across all sectors.

For further information please contact:

Zongshuai Fan

+44 (0)1223 766141zf272@cam.ac.ukNews | 6th February 2026

UK Manufacturing Dashboard: latest performance and global benchmarks

3rd February 2026

The Swiss paradox: a services reputation built on an industrial and innovation powerhouse

News | 21st January 2026

CIIP delivers bespoke training for delegation from the Government of Nigeria

Get in touch to find out more about working with us